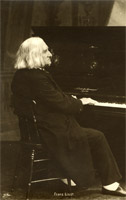

Franz Liszt

(1811-86)

Although he never played electric guitar or gave an interview to Rolling Stone, virtuoso pianist and composer Franz Liszt has often been called the world’s first rock star. His abilities were such that even those who disliked his compositions, such as Brahms, were dazzled by his performances. Liszt inspired near-fanaticism among his many admirers, who went to great lengths to obtain even the smallest souvenir. At the same time, he caused scandals by entering illicit relationships with two married noblewomen.

Youth and Early Studies in Vienna and Paris Youth and Early Studies in Vienna and Paris

Franz Liszt was born October 22, 1811, in Doborján, Hungary, today the town of Raiding in Austria. His father, Adam Liszt, worked in Doborján as a clerk for Prince Esterházy (the Esterházy family is perhaps most well known as the patrons of Haydn). His mother Maria Anna Lager came from a modest family, and before meeting Adam Liszt worked as a chambermaid in Vienna. Liszt had his first piano lessons with his father, who was an amateur musician. By age nine he was already receiving public acclaim for his performances, notably at the palace of Prince Esterházy.

In May 1822, with financial help from a few Hungarian aristocrats, the young Liszt was able to move to Vienna with his parents in order to study piano with Karl Czerny and composition with Antonio Salieri. Aware that his son’s talent was extraordinary, Adam Liszt took an unpaid leave of absence to make the move to Vienna possible. Moreover, Czerny and Salieri, equally aware of their new pupil’s potential, offered their services free of charge. Liszt rewarded their faith with extreme dedication, even though Czerny was very demanding on technical matters, such as scales, arpeggios, and the like.

Encouraging press reviews of his son’s performances convinced Adam Liszt to leave Vienna for Paris, hoping to further his son’s career in the French capital. The family arrived there in December of 1823, after three months of travel and numerous concerts given along the way. In Paris, Liszt studied composition with Ferdinando Paer and theory with Anton Reicha.

Like his piano playing, his compositions from this period were also notably successful. Liszt was only fourteen when the Paris Opéra agreed to perform his one-act opera Don Sanche. Shortly thereafter, the first version of his Etudes for piano was published in 1826. He continued playing concerts as well. Between 1824 and 1827, Liszt, accompanied by his father, performed extensively in France and toured England on three occasions. His fame was such that King George IV of England himself received Liszt for a private performance.

Depression and Healing Depression and Healing

In 1827 Adam Liszt died abruptly of typhoid fever. Liszt attended his father’s funeral alone, his mother having returned to Austria three years earlier to stay with family while her son was on tour. Liszt found himself charged with providing for the family and for reimbursing debts. He did so by working as a private piano teacher. While working in this capacity, he fell in love with a student his age, but the girl’s father cut the romance short, and immediately dismissed Liszt.

The combination of these events caused Liszt to have a nervous breakdown. He discontinued any music making and diligently frequented the church, even contemplating priesthood. His removal from society was such that it even led to rumors that he had died.

But Liszt could not ignore for long the exciting atmosphere around him. Witnessing the Revolution of 1830 in the streets of Paris, he was drawn to composing again and started to sketch a Revolutionary Symphony. Other talented composers also inspired Liszt, including Hector Berlioz. He met Berlioz and attended the performance of his Symphonie Fantastique in 1830. The friendship between them was to endure twenty years. In 1832, recitals by acclaimed violinist Niccolo Paganini and pianist Frederic Chopin also made a lasting impression on Liszt.

His years of seclusion were another source of his renewed interest in music. During this time, Liszt read a great deal. He was particularly engaged by readings on the relationship of music to other arts and the religious theories of Saint-Simon and the Abbe de Lamennais, whom he later traveled to meet in person. His extensive reading had another benefit: as he refined his literary tastes and fully mastered the French language, he began to participate in and to enjoy the artistic and intellectual vibrancy of the salons. It was probably in such a setting that he came to meet the countess Marie D’Agoult. In 1833, she and Liszt began a clandestine affair. For two years, it consisted mostly of correspondence and brief rendezvous. But in 1835, Marie became pregnant and left with Liszt for Geneva, Switzerland. There, Liszt offered his services as a piano teacher on the faculty of the newly opened conservatory. In December 1835, Liszt’s first daughter Blandine was born; Liszt officially acknowledged paternity, and was to do likewise for the two other children that Marie later gave birth to.

During these years Liszt did not perform publicly. After the death of his father Liszt shied away from the concert stage, but two events prompted his return to public performances. One was a piano duel that was organized in March of 1837 in Paris against the virtuoso Sigismund Thalberg. Thalberg’s reputation was growing and Liszt made the effort to travel back to France in order to reaffirm his supremacy as a concert pianist. After he returned home from Paris in the fall of 1837, Liszt took his family to Italy. A second daughter, Cosima, was born in Bellagio in December.

While there, the second event that encouraged Liszt to perform publicly was the news that a flood had ravaged Pest in Hungary. Even though Liszt had not spent a great deal of time there, he was very aware of his Hungarian roots. Thus, he left at once for Vienna in order to offer a series of relief concerts for the affected population. The funds he gathered exceeded any other private donation that was made to Hungary. From that point on, Liszt became a Hungarian national symbol. He warmly accepted and reciprocated the Hungarians’ affection, showing patriotism on several occasions by playing Hungarian tunes (while forbidden to do so by Austrian authorities) and by wearing a traditional Hungarian costume on stage. He also made use of popular tunes from the Magyar and Gypsy repertoires in his own music, notably in the famous Hungarian Rhapsodies. However, his lack of distinction between these two repertoires in his book The Gypsies and their Music in Hungary (1859) did earn a measure of hostility from some of his compatriots.

As Liszt’s desire to fully resume his career as a virtuoso performer grew, his relationship with Marie d’Agoult deteriorated. Their son Daniel was born in May of 1839 in Rome. Five months later, Marie d’Agoult returned to Paris, where she hoped to be forgiven by her family. She was indeed welcomed back, but her children were not, and they went on to be raised by their grandmother, Anna Liszt. Marie d’Agoult put an end to her relationship with Liszt in 1844. His long absences, his lack of fidelity, and especially, his lack of discretion, hurt her ego and her reputation more than she could tolerate. In a letter to him she stated, “I am willing to be your mistress, but not one of your mistresses.”

Unrivaled Virtuoso

While by the age of twenty-eight Liszt was already hailed as a virtuoso pianist, it was the years from 1839 to 1847 which really cemented his reputation as the most formidable  pianist of his time, and, arguably, of all time. pianist of his time, and, arguably, of all time.

During these years, called Liszt’s “Glanzzeit” period (Time of Splendor), the artist toured extensively. He traveled everywhere, from Dublin to Madrid, from Istanbul to Odessa and Moscow, giving over a thousand performances. The way the recitals were set has become a standard for performers today, but the format was truly innovative for the time. Instead of performing in salons and small venues, Liszt performed in large concert halls by himself. He played with his profile to the audience, and with the piano lid opened in order for the sound to carry. He memorized his programs entirely and played a repertoire ranging from Bach to his own works; he popularized several works of Beethoven, today standards, but at that time unknown.

Robert Schumann commented that Liszt’s own works, such as the Grandes études de Paganini and Etudes d’exécution transcendante, were so difficult that only a dozen pianists in the world could pretend to play them (Liszt later reviewed and simplified them somewhat). Indeed, Liszt particularly enjoyed dazzling his audiences with an unprecedented display of technique – notably furiously fast tempi, glissandi, and large leaps – but also with very expressive playing. A contemporary of new developments in piano making, Liszt truly pioneered the modern piano technique and offered his listeners a completely new experience in terms of piano performance.

Liszt’s audiences responded enthusiastically to his ability and to the new techniques. Early biographies of Liszt’s life enjoy describing the “Lisztomania” by giving a profusion of anecdotes, such as hysterical female admirers fainting or fighting over one of Liszt’s cigar stubs. Indeed, Liszt was admired everywhere. He had among his audience most of the kings and queens of Europe and received honors from them on many occasions. His last tour lasted eighteen months, took him from Austria to Ukraine, and included a stay in Turkey.

While he was in Ukraine, Liszt was hosted for three months at the estate of the twenty-eight-year-old Princess Carolyn of Sayn-Wittgenstein. They fell in love, and in February 1848, although already married, she left with Liszt for Weimar. There the position of kapellmeister had awaited Liszt since 1842; it was an opportunity for him to rest after eight years of intense traveling. Both the stability of his life in Weimar and the orchestra available to him in the city allowed Liszt to devote time to composition and most of his major orchestral works come from this period.

In Weimar he wrote twelve symphonic poems, the Faust and Dante symphonies, the Messe de Gran, the Psalm XIII, as well as numerous piano works (the concertos, the sonata, the Album d’un voyageur, and the final versions of the Etudes and Hungarian Rhapsodies).

Revered as a pianist, Liszt quickly established his reputation as a gifted conductor as well. He was frequently invited to conduct performances throughout Germany. In Weimar he championed the works of Wagner and Berlioz. And in his residence at Altenburg Liszt received numerous artists and students eager to benefit from his knowledge as a pianist and conductor and to share his ideas about music.

However, the situation in Weimar also had its share of dissatisfying elements; ultimately, local intrigues and jealousies led him to resign from his position in 1858. Another source of personal discontent was the lingering situation of Princess Carolyn’s request for an annulment, which eventually led the couple to leave for Rome in order to seek the direct assistance of the Pope in the matter.

Rome

In 1861, Carolyn thought her thirteen-year fight to annul her marriage had finally ended. Her annulment was granted and her marriage to Liszt was scheduled to take place in Rome that October. However, the plans were ruined at the last minute by the interference of Carolyn’s family, which was concerned that her daughter from her first marriage would lose her rights to the family property were Carolyn to remarry. Along with this major disappointment, Liszt was confronted at the same time by the loss of two of his children, Daniel in 1859 and Blandine in 1862. As for Cosima, her decision to leave her husband for Richard Wagner caused lasting discord between her and Liszt.

This series of hardships affected Liszt in a way similar to that of the death of his father. He isolated himself and sought comfort in the church. As Rome was the center of religious life in Europe, Liszt decided to stay in the city. However, he did not give up music altogether. He composed more piano music and worked on his two oratorios Legende von der heiligen Elisabeth (The Legend of St. Elizabeth) and Christus, which both took numerous years to complete. He frequented the church for musical inspiration as well, and was especially seduced by the music of Palestrina, as well as by Gregorian chant. This series of hardships affected Liszt in a way similar to that of the death of his father. He isolated himself and sought comfort in the church. As Rome was the center of religious life in Europe, Liszt decided to stay in the city. However, he did not give up music altogether. He composed more piano music and worked on his two oratorios Legende von der heiligen Elisabeth (The Legend of St. Elizabeth) and Christus, which both took numerous years to complete. He frequented the church for musical inspiration as well, and was especially seduced by the music of Palestrina, as well as by Gregorian chant.

It is hardly surprising then, that Liszt came to sympathize with the Cecilian movement and its founder Franz Xaver Witt. From 1863 to 1865, Liszt isolated himself at the monastery of Madonna del Rosario, near Rome. There Pope Pius IX himself, who was an admirer of Liszt's music and who later invited Liszt to give private recitals at the Vatican, visited him. Following his retreat, Liszt entered the clergy in the minor orders.

At the end of 1866, Liszt took an apartment in Rome and resumed his activities as a piano teacher. At the request of the Grand Duke of Weimar, Liszt also resumed some of his work in the city of Weimar, starting in 1869. The Grand Duke provided him with housing, and Liszt offered a regular masterclass in the city from the spring to the fall. When neither in Weimar nor in Rome, Liszt could be found in Budapest, where he was honored in 1871 with the title of Royal Hungarian Counselor for the Emperor Franz Joseph. Four years later, he was also named president of the recently founded National Hungarian Royal Academy of Music. Liszt took a more active role in the latter position than in the former, setting the curriculum and requirements for the new establishment. As it was hoped, the academy considerably helped Hungarian talents such as Bela Bartók and Zoltán Kodály.

Final Years

Liszt spent the last years of his life traveling continuously. In 1886, the year Liszt turned seventy-five, he was invited to attend festivals honoring him in several countries. On the insistence of a former student, he chose to visit England, a country he had avoided for over forty years because of an unsuccessful tour during the Glanzzeit period. Although Liszt considered himself no longer fit to play, he was urged to perform several times by his admirers, who included Queen Victoria.

Liszt returned to Weimar satisfied, but in a weakened state of health; he was by then almost blind. His daughter Cosima, with whom he had reconciled, requested his presence in Bayreuth, where the festival devoted to the late Wagner was experiencing difficulties. On his way to Bayreuth by night train, Liszt caught pneumonia. In Bayreuth, he was tended to by the faithful students who followed him on his journeys, as well as by his daughter. Over ten days his condition worsened and Liszt died on the morning of July 31, 1886.

References:

Haraszti, Emil. Franz Liszt. Paris: Éditions A. et J. Picard et Cie, 1967.

Liszt, Franz. Letters of Franz Liszt. Ed. La Mara. Trans. Constance Bache. New York, Greenwood Press, 1969.

Walker, Alan. Franz Liszt. New York: Knopf, 1982.

Walker, Alan: 'Liszt, Franz [Ferenc]', Grove Music Online ed. L. Macy (Accessed 24 January 2006), <http://www.grovemusic.com>

Williams, Adrian. Portrait of Liszt : By Himself and His Contemporaries. New York : Oxford University Press, 1990. |