Frédéric Chopin

(1810-49)

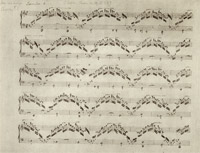

Written when he was only seventeen years old, Frédéric Chopin’s Variations on “Là ci darem” from Mozart’s Don Giovanni, Op. 2, for piano and orchestra, is not considered one of his most interesting works. Nevertheless, when Chopin’s eminent contemporary Robert Schumann heard it, he was in no doubt as to Chopin’s talent. In his first published essay of music criticism (1831), Schumann hailed Chopin with the famous remark, “Hats off, gentlemen, a genius!” and Chopin’s career was launched.

Childhood in Warsaw Childhood in Warsaw

Fryderyk Franciszek Chopin was born near Warsaw in Zelazowa Wola, Poland on

March 1, 1810. He later adopted the French variant of his name, Frédéric-François, when he moved to Paris. He was the second of four children and the only boy born to Mikolaj Chopin and Tekla Justyna Kryzanowska. His father had moved to Poland in 1802 in order to teach French to the son of Countess Justyna Skarbek, which is where he met Chopin’s mother, who was the companion and assistant to the countess. In 1810, when Chopin was just seven months old, the family moved to Warsaw, where his father had secured a position in the recently established high school.

Because of his father’s position at the academy, the Chopin family began to mingle with elite circles of Warsaw society. The family mixed easily with members of the intelligentsia, the middle gentry (many of whose children were students at the high school), as well as a few members of the wealthy aristocracy.

Did You Know...?

Chopin's Funeral March (from Sonata 2, Third Movement) has become part of our collective consciousness as a musical metaphor for death. It has been used in a number of films including Fanny and Alexander ( 1982); Angel Heart ( 1987); A Prayer for the Dying ( 1987); Beetlejuice ( 1988); and Space Jam ( 1996).

From the ages of six to eleven, Chopin received piano lessons from Wojciech Zywny, whose main instrument, interestingly, was violin. Zywny gave the boy a firm grounding in Bach and the music of the Classical period, but it soon became apparent that the gifted young boy had outgrown the abilities of his teacher. When Chopin entered the High School of Music in 1826, he continued his piano instruction with the school’s rector, Jozef Elsner, and started organ lessons with Wilhelm Würfel. When it came to technique, his teachers left him to his own devices, since Chopin had a natural aptitude for it, but he still received rigorous training in composition during his high school years.

It was clear to all of his teachers that Chopin had exceptional talent and was a musical genius. There was little left in Poland for the young virtuoso to learn. Following his graduation, he traveled to Vienna and gave two very well-received concerts. Upon his return to Warsaw, he began performing regularly in salons and occasionally gave bigger concerts. In December of 1829 he gave the first performance of the Piano Concerto in F minor and in March of the following year premiered the Piano Concerto in E minor, both of which met with great success. Since he was uncomfortable with the idea of pursuing a concert career, Chopin questioned his available career options. Young and in pursuit of new adventures, on November 1, 1830, Chopin and a high school friend, Tytus Wojciechowski, journeyed to Vienna to begin what was meant to be a grand tour of Europe.

One week after arriving in Vienna, the two young men heard news of an uprising in Warsaw, sparked by a failed attempt to assassinate the Grand Duke Constantin of Russia, ruler of Poland. Russia’s superior forces quickly subdued the revolt. In light of these events, feeling that he might be needed, Tytus decided to return to Poland, leaving Chopin alone in Vienna.

While in Vienna, Chopin traveled in a small circle of friends, attended various concerts and wrote the first nine mazurkas, opus 6 and opus 7. Though active as a musician, he was still unclear about what this future might hold and suffered bouts of depression. Eight months later, in July of 1831, Chopin left Vienna and headed for Paris.

Within two months, Chopin was feeling quite at home in Paris’s vibrant cultural life. His music and his performances soon came to be regarded highly, even among the elite of Parisian performers. He became friends with an extraordinary group of young artists, including the pianist-composer Franz Liszt and composer Hector Berlioz.

By the end of 1832, Chopin’s various social connections opened up another career path for him. Although he had been earning some income from private performances and sales of his published music, there was also a great demand for him as a teacher. His reputation as a performer grew as well, despite his eschewing of public concert halls. Both his delicately crafted music and his sensitive, nuanced playing style seemed more suited to the salon than to the concert hall. As a composer his fame was also increasing, and, by 1833, his music was being published in France, Germany, and England.

The following year, Chopin eased into a consistent routine of teaching, composing, and private salon performances. In the 1834-35 season, Chopin performed two major concerts of his works, which were very well received. Nevertheless, for the next several years he refused many invitations for public concerts, preferring to view himself as a composer.

With his life and career going so well, Chopin did not have much desire to return to Poland, but he did miss his family, so in 1835 he met up with them and spent the summer in Karlsbad. On his way home, he made a stop in Dresden to visit with friends of his family. While there, he fell in love with the sixteen-year-old daughter of the family, Maria Wodzinski. During the following summer of 1836, he spent five weeks on holiday with the Wodzinski family in Marienbad. On his last night with the family, he proposed to Maria. Though he was not given the family’s outright consent, Maria’s mother implied that the marriage would likely take place. However, the next year, 1837, he received a letter from the Wodzinski family that dashed his hopes of marrying Maria.

In April 1838 Chopin became reacquainted with the writer George Sand, whom he had met once before. This time, however, there was a mutual attraction, and the two became lovers by summer. That winter Chopin, Sand, and her two children traveled to Majorca in order to get away from the city and to avoid some unpleasantness with Sand’s previous lover. The cold, damp winter months wreaked havoc on Chopin’s health. He was diagnosed with tuberculosis, which left Sand in the position of caregiver. In April 1838 Chopin became reacquainted with the writer George Sand, whom he had met once before. This time, however, there was a mutual attraction, and the two became lovers by summer. That winter Chopin, Sand, and her two children traveled to Majorca in order to get away from the city and to avoid some unpleasantness with Sand’s previous lover. The cold, damp winter months wreaked havoc on Chopin’s health. He was diagnosed with tuberculosis, which left Sand in the position of caregiver.

In spite of the difficulties, both Chopin and Sand remained productive with their respective writing. By late January, however, Chopin’s deteriorating health prompted them to leave the island. From Majorca they traveled to Marseilles for an extended period of convalescence. By May of 1839, Chopin had recuperated enough that they could spend the summer months at Sand’s home in Nohant, France.

The End of Chopin and Sand's Relationship

After the summer of 1839 Chopin began to miss the atmosphere of the city, so by October Sand and Chopin had moved back to Paris. By renting adjacent flats in the Pigalle, the pair was able to maintain their relationship, as well as a degree of independence. Their relationship was not without its problems, largely caused by the differences between their respective circles of friends. Chopin had many “society” friends, while Sand associated with a more bohemian, artistic, and political crowd. The two felt uncomfortable in one another’s circles. Nevertheless, their relationship provided Chopin with a sense of stability. He remained productive, continuing to teach and to compose.

It was in this period that he refocused on composition and produced music of an even higher quality. Chopin and Sand spent every summer together in Nohant, during which time Chopin arduously composed. His music became increasingly rich and complex, but the compositional process became tedious and slow.

Chopin’s health started to deteriorate again in 1844. This ill health, coupled with his personal frustrations over his lack of fluency as a composer and growing tensions with Sand and her children, brought their relationship to an end. Sand’s novel Lucrezia Floriani, published in 1846, depicts the breakup of a couple’s relationship and is thought to be largely autobiographical. By 1847 Chopin and Sand’s relationship was over.

Death at an Early Age

Chopin continued to give lessons and the occasional private performance, but his health was getting worse. When the 1848 Revolution broke out in Paris that February, Chopin deemed it a good time to leave the country. With his Scottish pupil Jane Stirling helping him financially, he embarked on a tour of England and Scotland. Chopin gave concerts and made the rounds of high society, but these activities began to wear on his already delicate health. At the same time, it became apparent that Stirling was hoping to fill the space left by Sand, but Chopin felt “closer to the coffin, than the marriage bed,” as he put it.

Returning to London from a trip to Scotland, Chopin weighed less than 100 pounds. His doctors urged him to return to Paris as soon as possible. After performing a few more concerts in London, he did so. It was clear that Chopin was in the final stages of tuberculosis. His many friends visited him often and Stirling offered financial assistance, but he was most pleased that his sister Ludwika and her family came to live with him, providing the family atmosphere that he craved. Chopin passed away in the Place Vendôme on October 17, 1849.

References:

Baker, Theodore. The Concise Baker’s Biographical Dictionary of Musicians. 8th ed. Rev. Nicolas Slonimsky. New York: Schirmer Books, 1994.

Goulding, Philip. Classical Music: The 50 Greatest Composers and Their 1,000 Greatest Works. New York: Fawcett Books, 1992.

Schonberg, Harold. The Lives of the Great Composers. 3rd ed. Rev. Nicolas Slonimsky. New York: W.W. Norton, 1997.

Michalowski, Kornel and Jim Samson: ‘Chopin, Fryderyk Franciszek’, Grove Music Online ed. L. Macy (Accessed 8 February 2006), http://www.grovemusic.com |